The following is an adaptation of a presentation which I had the honor of giving at the International Disability Rights Affirmation Conference 2013 on 2013-09-27.

Accessibility In Mind represents a fundamental approach to resolving accessibility problems. 'Fundamental' in the sense that it addresses the causes of the accessibility problems, as opposed to continuously resolving their recurring effects.

Who am I to be talking to you about accessibility?

In real life, I've worked for a local organization that audits the accessibility of buildings. We've even done a course to make sure we'd cover all the bases. After all, we don't want to end up accounting only for the needs of people in wheelchairs.

While working for this local organization, I began to realize that something was missing in our approach. We went from place to place, and from building to building, collecting information about what accessibility problems needed resolving. We never found out if this information was passed on to the architect of the building, let alone if any architects were offered the opportunity to learn from this. With this explanation I hope to clarify the benefits to you.

One of the goals of Accessibility In Mind, is to address this situation. Another goal is to draw attention to the situation in countries where people with disabilities don't even get the chance to show how they could benefit society.

All of you who read my website may live in countries, where people with disabilities are seen as equals (for the most part), and accessibility to public buildings is quite good.

Now, don't tell me. Let me guess.

You think the situation in your country is bad.

Well, unless you know something I don’t, believe you me...

You ain’t seen nothin’ yet!

Also, when I get to the situation in Turkey, you'd better prepare for a shock. Throughout the world, people's awareness of the needs of people with disabilities varies from excellent to non-existent - and I didn’t say "almost."

Some countries are doing comparatively well, but there’s room for improvement even there.

Let's start with the worst countries - countries where people with disabilities have (for all intents and purposes) been forgotten.

I've watched a documentary about North Korea, which revealed that, in that country, people with disabilities "are encouraged to stay indoors", probably because "they don't fit in the desired picture."

I've also watched a Turkish video, the English title of which was something like 'The Forgotten One.' It featured a young lady in a wheelchair that was too big for her. She tried some things at home which didn't work out. Later she was outside where she could hardly get anywhere herself. She asked some passersby, at least one of whom just walked on, although they looked quite capable of helping her.

It's been quite a few years already, but to this very day, I remember how this video ended. The young lady rolled out of view, and only seconds later...

...there was a gunshot.

These videos paint a pretty dire picture of the situation in these countries, and these may not be the only countries in such a bad state. For people in countries that are doing better, it's easy to understand why people with disabilities living in such countries cannot make themselves useful.

These countries show all the signs of people in power considering people with disabilities useless. Let me be honest: in such countries, people with disabilities are useless. However, this is only because the infrastructure in these countries is deplorable.

What will it take to make the people in power in these countries...

The disabled people among us can serve as examples of the latter. I'm pretty sure quite a few people with disabilities have (or have had) work, paid or voluntary, despite having a disability.

People in power in the affected countries may argue that the required steps would take time, effort, and money. They might also wonder why they should invest in people with disabilities, who (in their view) have already shown that they are useless. However, surely it stands to reason that they'll be rewarded. There's a Dutch saying that goes, "vele handen maken licht werk".

It means, "many hands make light work."

Why shouldn't some of these 'hands' belong to people with disabilities?

Once countries take steps to engage their disabled community, they may well find an extra hurdle to overcome, called Learned Helplessness.

For those of us who are unfamiliar with this term...

'Learned Helplessness' refers to the inability of people to see what they can do.

This happens to people who have been helpless for so long, they no longer see what potential they have. To put it perhaps a bit too strongly, they will "have gained a talent for dependence."

That quote was from Kes, in the first episode of Star Trek: Voyager, entitled Caretaker.

Let's get back to reality.

Countries where people with disabilities are (for all intents and purposes) forgotten, should be able to present some great progress, once the people there remember the 'forgotten ones.'

As I mentioned earlier, even the best countries could do with some improvements. For this to happen, there are two vicious circles we need to escape from, which continue to cost us time and money.

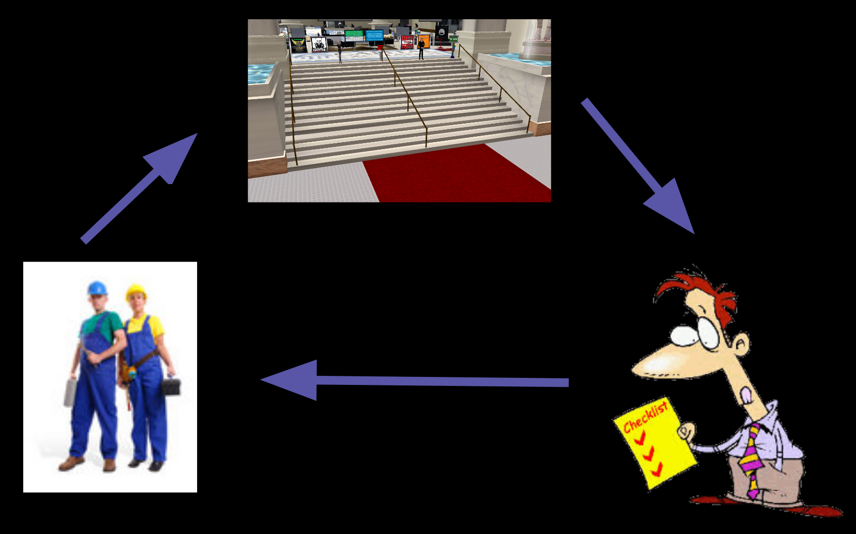

The first vicious circle that I'd like to describe, concerns new buildings.

New buildings still tend to be created with accessibility leaving to be desired. Organizations are then contacted to report on what needs to be done to correct these problems. The accessibility problems are then corrected, so one might be forgiven for thinking that the problem is solved. The thing is...architects are left unaware of the changes that needed to be made to their creations. As a result, with the next building they create, they're bound to repeat their mistakes.

This vicious circle can be dissolved by drawing the attention of architects to the information they need to prevent them creating accessibility problems in the first place.

Architects can access this information already, but they don't know they need to. Remember, I said earlier that architects are left unaware of the changes that needed to be made to their creations.

Architects might not only be hindered by lack of expertise. They might also see accessibility guidelines as impairing their creativity. Case in point: something known as 'compositional hierarchy' would be a no-no. To put it perhaps a bit more crudely than an architect would, 'compositional hierarchy' refers to creating height differences where it's not really necessary.

Architects may be opposed to abandoning such things, but the alternative is that people with possibly little or no sense of the intended design, resort to impairing the beauty of the architect's creations. And let's go back to the auditor. Architects not following accessibility guidelines is also what made the audit necessary, and it's also what made the auditor necessary. I do like that this work gets me out the door, but I don't like that it is necessary.

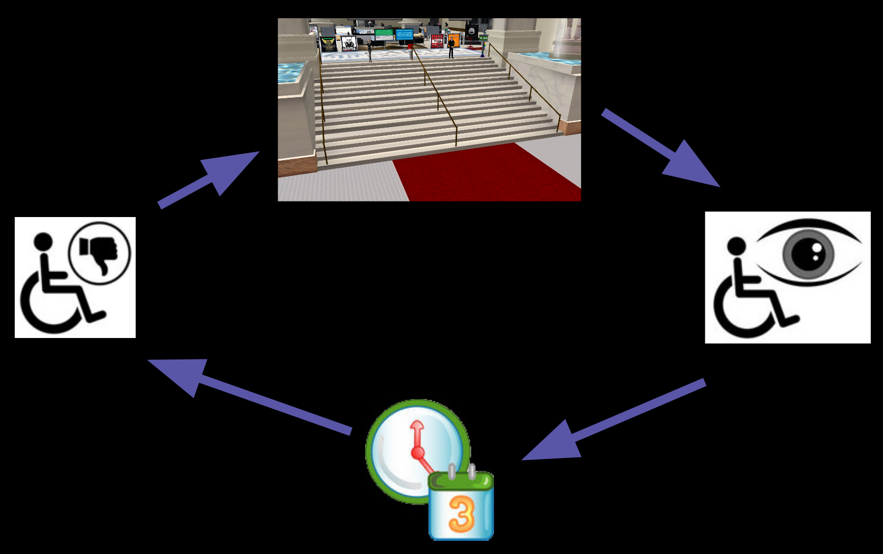

The second vicious circle I'd like to describe, concerns existing buildings.

Managers of public buildings with accessibility problems may want to have these problems corrected, only if they see enough people with disabilities wanting to use that building. The problem here is that, by the time managers check how many people with disabilities would like to use a building, people with disabilities may already have forgotten about that building, and so, the managers of these buildings see no reason to improve the accessibility of that building. As a result, managers don't see people with disabilities wanting to use a building. They don't seem to understand that people with disabilities might come back, once they see that they can access that building without any problems.

So, what's the lesson here?

If managers judge too late the interest of people with disabilities in their buildings, then these managers may themselves be the very reason why accessibility problems are never resolved. That is, until these managers understand the vicious circle I just explained.

I promised you a solution to the problems faced by even the best of countries. My solution is for all of us to share the insights presented on this page; present it to architects, architecture professors, policy makers, planners...anyone who can apply it to what they design or build in the future.

Maybe you could even arrange for the right people to experience life with a disability for a day or more.

If you'd like to help me address the accessibility issue the AIM way, I invite you to consider the following questions:

One suggestion that was shared during the presentation, was to make Universal Design a required course for architects and city planners.

...or, is it...? This is the end of the text I used for my presentation, which I'm actually still adapting for this page. I will be incorporating the reflections my audience shared during my presentation.

Question: What about historic structures? Do history and original design lose to accessibility?

Answer: It depends on how important the present design of the building is. Why would people want to maintain the lack of accessibility? How many people with disabilities would like to or need to access that building?

I received the comment saying "there are metal foldable ramps, etc. that can be installed to existing buildings."

I've seen them and I have nothing against them, but Accessibility In Mind is about getting people to build buildings and construct the surrounding area, such that everything public is accessible out of the box.

Suggestion: Make a course in retrofitting historic buildings compulsory in architectural schools.

I remember someone saying, "NO offense to the speaker, I would be happier if they made the side walks flat so I can wheel my chair"

No offense taken, and I agree.

There was talk among the audience about rules, laws, and what not.

By sharing my insights, I hope to make people plan and build with accessibility in mind, not because they have to, but because they want to; because they see the benefits not just for people with disabilities, but for everyone.

Someone asked who watches the auditors, and I have to admit, I have no answer. The (disabled) users of buildings and areas, maybe...?